Making “the People”: Political Imaginaries and the Materiality of Barricades in Mexico and Latvia

Iván Arenas. Address for correspondence: Department of Anthropology, University of California, 232 Kroeber Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. iarenas@berkeley.edu.

Dace Dzenovska. Address for correspondence: Faculty of Humanities, University of Latvia, Visvalža iela 4a, Rīga LV 1050, Latvia. dace.dzenovska@lu.lv.

We would like to thank Charles Hale, Cindy Huang, Katherine Lemons, the two anonymous reviewers, as well as the editors of this special issue of Laboratorium on Latin America and the former Soviet Union for reading and commenting all or parts of this paper. Research in both Mexico and Latvia was enabled by the generous support of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States. Finally, we extend our deep gratitude to colleagues, friends, and collaborators in Mexico and Latvia, without whom this research would not have been possible.

History begins at ground level, with footsteps.

Michel de Certeau. The Practice of Everyday Life, 1984

In 2006, improvised barricades went up in the Mexican city of Oaxaca to defend the city’s residents and members of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca from paramilitary incursions and police repression. Composed of everything from appropriated buses to nails, sticks and string, and organized and protected by housewives and young kids from urban crews, the Oaxacan barricades cultivated an intimate and effervescent sociality of el pueblo (the people). Fifteen years earlier, in 1991, the Latvian tauta (the people or Volk) also constructed barricades in the streets of Rīga to shield themselves and important landmarks from Soviet military units. Like the barricades in Oaxaca, those in Rīga cultivated an intimate sociality of the people. Both were also made possible by and gave rise to historically specific political imaginaries and collective identities.

As a revolutionary technique, barricades have an established history. The most famous instance is in France, where the popular use of barricades in civil urban insurgency had its beginning and where, following the French Revolution of 1789, barricade building prevailed for almost a century (Douglas 2008, Traugott 2010; 1993).[1] Recently, Carl Douglas has argued that the barricade, as a form and practice of urban insurgency, changed the physical and social landscape of Paris. Here, the practice of barricade-building, where “passers-by were each invited to contribute a paver” meant that “construction became a means of […] converting observers into participants” (2008:39). Douglas contrasts the collective subject created by the barricades with the individual bourgeois subject that Haussmann’s boulevards privileged. He concludes that transformations in state military power, combined with the broad thoroughfares of modern Paris, indicate that barricades and the collective subject they conjured up have become an outdated, if not altogether extinct, revolutionary technique. The Latvian and Oaxacan cases suggest, however, that barricades continue to be part of the political imaginary and practice of resistance in moments of crisis.[2]

In their differences from and similarities to each other and to the barricades of Paris, these cases also suggest that rather than being merely a revolutionary technique, barricades and the collective subject positions they produce are a historically and culturally specific assemblage of political imaginaries, spatial and material practices, and social relations. In this paper, through an ethnographic engagement with the spatial and material practices of Latvian and Mexican barricade building, we will consider the intertwined relationship between materiality, human praxis, and politics, as well as the political possibilities and limitations that such concrete articulations engender.

This conversation between Mexico and Latvia is shaped by both contingency and a concerted effort to contemplate what, if anything, a joint consideration of events in Mexico and Latvia can tell us about the enduring social and political force of intensely lived but fleeting moments. Both of us have spent a significant amount of time in Latvia and Mexico doing our own research or supporting the other’s research, thus making this conversation possible. More importantly, as we understand it, the editors of this special issue of Laboratorium argue that a comparative perspective between Latin America and the former Soviet Union may result in novel ways of thinking about narratives and practices of transformation, as well as offer insights into the historical and discursive relationship of both regions with the West. For us, this conversation between Mexico and Latvia is shaped by a related if different positioning of both countries with regard to modernity and the West. Thought of as being “not quite there” on a global scale, both have been subject to neoliberal market reforms and democratization discourses and practices. Through our engagement with the barricades, we also aim to open some avenues for considering the different imaginations and practices of “there” that were conjured up during barricade building in Latvia and Mexico. Themselves a product of contingency, as the barricades in Latvia and Mexico reshaped the social landscape, they also produced alternative politics that, even if seemingly short-lived, continue to be relevant in both countries not only in terms of how people view the past, but also for how they envisage the present and future.

From the Abstract to the Concrete: Articulations of Space, Materiality, and Politics

Whether attributed to the work of Henri Lefebvre (1974) or Michel Foucault (1982), many have characterized the last decade’s preoccupations with space as marking a spatial turn in theory. Indeed, space seems to be all around us. The writings of Lefebvre and Michel de Certeau’s (1984) focus on the practice(s) of everyday life established that space is always in production, that as much as space may shape the parameters of our actions, it is in turn shaped by our actions. From Edward Said’s (1978) imaginative geographies to Liisa Malkki’s (1995) focus on how discourses of self and social become rooted in particular times and spaces, scholars have argued for the importance of narratives and selective imaginations to the production of space. Many authors would thus agree that the landscapes in which and through which we forge our individual, subjective, and collective identities are the result of the dynamic relationship across time of an always particular and contested socio-spatial interweave at any given site (where the site may be construed at any scale, from that of a room or city to that of a nation or the globe). Nonetheless, if it has become commonplace to say that space is more than just a battlefield for competing ideologies, the way in which it is an active participant in processes of social transformation is less clear. If there is no such thing as a static or fixed space, and if our subjectivity is constructed in and through this socio-spatial interweave, for us the question remains: how is space a consequential actant (to use Bruno Latour’s terminology, 1999) in processes of the formation of particular social relations and political subjects?

Undertaking an archaeology of contemporary material culture, recent work on materiality has productively challenged the entrenched binary and commonplace hierarchy between things and thoughts (Miller 2005). In focusing on subject-object relations at the scale and scope of the everyday, it seems to us that materiality scholars offer another avenue by which to approach the mutually constitutive relationship between spatial practices and the production of political subjectivities. Or, to put it another way, we hope to show how focusing on subject-object relations in the building of barricades can illuminate processes through which people, material practices, and spaces are articulated into lasting social and political formations through short-lived practices.[3] Interested in how these articulations may also produce particular political subjectivities, at the same time as we turn to materiality, we have also found it relevant to revisit—or redeploy—Louis Althusser’s concept of interpellation (1970). Though often overlooked, Althusser focused the majority of his essay describing interpellation not on the paradigmatic moment of a policeman hailing someone on the street, but on the role of Ideological State Apparatuses (such as church or school) in delineating the material practices that come to define expectations about the appropriate behavior and beliefs of particular subjects (priest or student, for example). Internalized and enacted by individuals, these expectations are critical to the iconic moment of interpellation, which is, after all, a relational moment between someone who hails an individual as a particular subject and that individual recognizing herself as that subject. We argue that it is not only individuals who do the hailing, but that space also has the capacity to hail, that, as a social-material formation, space plays an important and dynamic part in the process of transforming particular individuals into subjects. Moreover, it is our contention that in the process of interpellation, it is not only individuals who are hailed as subjects, but also collectivities of individuals, or, more precisely, individuals as members of particular publics (see also Butler 1997, Warner 2005).

Though this theoretical work undergirds what follows, we take it as a point of departure rather than as a point of arrival. In doing so, we follow Karl Marx’s insistence to advance from the abstract to the concrete (Marx 1977 [1857], Hall 2003).[4] In his general introduction to the “Grundrisse,” widely known as the “1857 Introduction,” Marx reflects on the notion of “production in general” to make this methodological point. Marx’s argument is that some form of production occurs in all historical periods and places, and one can therefore say that there is something in common between them. He further suggests that this identification of a common element—“production in general”—is a mode of abstraction which should be the starting point for further scientific inquiry that considers the specific mode of production characteristic of a concrete time and place. This entails tracing all the historical determinations—“the specificities and the connections”—that make up this concrete situation (Hall 2003). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to trace all the specificities and connections that make up the barricades and their associated political subjectivities in Latvia and Mexico, we do want to move beyond the generalization that there is a mutually constitutive relationship between material and spatial practices and political subjectivities, and investigate the concrete articulations of this relationship in their historical and political complexity.

In the following sections on barricade sociality in Rīga and Oaxaca, advancing toward the concrete enables us to show the historically formed differences between the barricade events in Latvia and Mexico, as well as to argue for their importance in creating collective social identities with transformative political possibilities. Thereafter, a brief review of the Latvian state’s handling of the citizenship question illustrates how this barricade sociality has been transformed through state-building practices. An ethnographic engagement with competing public identities in Oaxaca in the aftermath of the barricades illustrates the continued relevance and presence of barricade sociality today. We conclude by underscoring a shared sentiment and observation about the salience of this recent moment of barricade building to speak to contemporary scholarship and popular understandings of the foreseen triumph of representative democracy and capitalist markets. This is crucial in a current historical moment when, given the demise of the Soviet Union, the demonization of Latin American populist nationalism (such as that of Hugo Chavez), and cautious suspicion of hybrid governments like Brazil’s, little else seems politically possible or socially plausible.

Barricade Sociality and the Imaginary of the Nation in Latvia

“This morning I have a barricade feeling,” said Aina on a July morning in 2007, as she stood inside a mesh fence enclosure surrounded by a police cordon, waiting for the beginning of the third lesbian and gay pride parade in Rīga. The previous two attempts at holding pride parades generated widespread negative sentiment and violent protests that took the form of verbal assault, spitting, and the throwing of eggs and human excrement. In 2006, the parade itself was banned by the Rīga City Council two days before it was scheduled to take place, though seminars, discussions, film screenings, and an indoor pride celebration did occur as part of the broader Gay and Lesbian Friendship Days. Even as they found themselves enclosed by a protective mesh fence and a police cordon, many of the 2007 pride participants were concerned about the course of events. To illustrate the atmosphere of fear and anxiety, Aina invoked the barricades of January 1991, which people of all walks of life constructed to protect the (re)emerging polity from Soviet military units attempting to prevent the dissolution of the USSR.[5] The reference to the barricades, more specifically to “a barricade feeling,” also served to mark what she saw as the profound political and existential consequentiality of the gay and lesbian pride parade that made her attend the event despite the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty surrounding it.

Aina was not the only one who invoked the barricades during the controversy surrounding gay and lesbian activism. Several other gay and lesbian activists and their supporters also invoked the independence struggles, of which the barricades were an important element, to suggest that the political possibilities of that historical moment had been betrayed during the following years of nation- and state-building. Rita Ruduša, then-editor of the online policy portal Politika.lv, commented on the widespread negative sentiment toward the public and political visibility of gays and lesbians as follows: “We all stood there together on the riverbanks and said ‘For your freedom and ours.’ It seemed that people really believed this slogan of the Awakening, which was a simple sentence. But suddenly, 15 years later, it turns out that this simple sentence has all sorts of supplements. For your freedom and ours, but only if you are just like us” (Nagle 2007).[6]

Almost two decades after their erection, the barricades continue to shape the political imaginary, as well as the commemorative landscape in Latvia. In addition to flashing up in “moments of danger” (Benjamin 1988 [1950]), such as the controversy around the public and political visibility of gays and lesbians, the barricades are also reconstituted through commemorative events and reinscribed in the urban landscape through planks, monuments, and at the Museum of the Barricades where visitors can view photos and videos and listen to radio broadcasts from the barricade days while sitting on makeshift benches and cement blocks around an artificial bonfire site. An architectural model of the Old Town stands askew in the corner. Here, bonfire sites, huddled bodies, and barricade structures dot the landscape between the buildings in order to give visitors a sense of the barricade experience. The vibrant life of the barricades in the present suggests that they are more than a revolutionary technique that has been historically deployed in civil wars and urban insurgencies. They are also more than a moment in the political history of the state or an element of the collective self-narrative of the Latvian tauta. Importantly, the barricades have become a marker of a moment with seemingly endless political possibilities against which the present life of the people and the state of the polity are often assessed.

Though narrated as a time of unlimited possibilities, the political potential that the Latvian barricades engendered was also subject to historical determinations that gave it concrete form. While the Latvian Supreme Soviet had voted for independence from the Soviet Union in May of 1990, the government adopted a strategy for gradual transition to independence.[7] Thus, in January of 1991, Latvia was not entirely independent from the Soviet Union and it could be said that by constructing barricades citizens rebelled against the ruling regime and its military forces. In fact, some of the recollections of the barricades use such rhetoric when stating that “we all had a common enemy. We did not have anything to fight over. And the enemy was not the Russians. The Russians were also on the barricades in Rīga and Liepāja. Our enemy was the system which made us all into slaves” (Kazans 2008). This same statement, however, also entails traces of another kind of political imaginary that structured the barricade moment, namely that of the national self-determination of the Latvian tauta (people or Volk). In an important way, barricade-building practices in Latvia were animated by a political imaginary of a nation struggling for independence against an oppressive force, which sometimes was conceived as a totalitarian state and sometimes as Russian imperial expansion. It was precisely this articulation of both political subjectivities—of people as a democratic collective entity struggling against a ruling regime and of people as a nation (or Volk) struggling against political and cultural domination—that shaped the specific material and spatial practices of the barricades in Latvia, as well as the ensuing political imaginaries and possibilities.

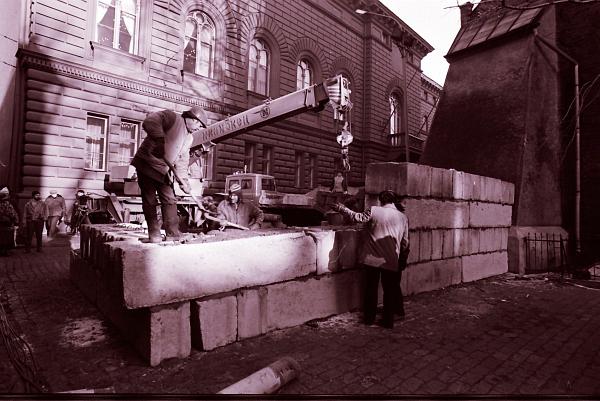

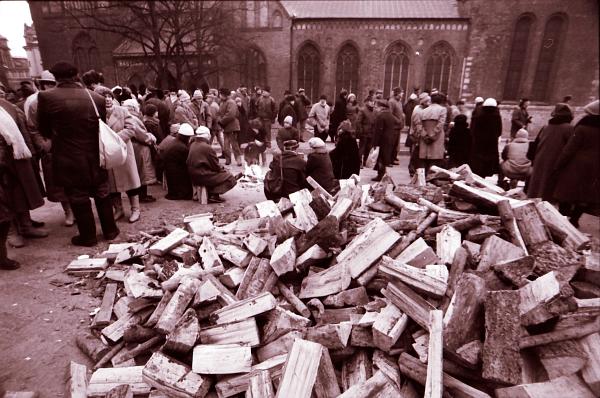

For example, rather than erupting en masse all over the city, as was the case in Paris (Douglas 2008) and also in Oaxaca (see the section below), the Latvian barricades were built in and around strategic sites such as television and radio broadcasting stations, bridges, the Old City, and the parliamentary building, where the Supreme Soviet of the Republic of Latvia had voted for independence in May of 1990. In response to reports that Soviet military forces were preparing an assault to prevent the dissolution of the USSR at a time when the world’s attention was focused on the first Gulf War in Iraq, in a radio address, Dainis Īvāns, leader of the Popular Front—a moderate political force at the forefront of the independence movement—invited people from all over Latvia to come to the capital and help defend the re-emerging nation. Consequently, people from all corners of the country made their way to Rīga in tractors, trucks, and buses, carrying logs and farm equipment with them. Identifying with the re-emerging nation, workers of Soviet collective farms and industrial complexes used the Soviet state’s heavy machinery for the purpose of bringing barricade materials, such as wooden logs and cement blocks, to the capital city where teams of construction workers used cranes to create the barricades (Images 1 and 2).

The concentration of the barricades in Rīga, the movement of rural residents to the capital city to help with the barricades, as well as the prominent presence of the Latvian national flag, point to the centrality of the imaginary of national-self determination in barricade construction in Latvia.[8] Rather than extensions of neighborhood life, as in the case of Oaxaca in 2006, as well as 19th century Paris,

|

|

barricades in Rīga were an articulation of the emerging nation. However, while many, if not most, of the barricade participants were of Latvian origin, other residents of Latvia, including Russians, were also on the barricades. The Popular Front had appealed to the Russian-speaking population in hopes of garnering the necessary popular support for a peaceful transition to independence; however, many Latvians did not necessarily expect to encounter Russian-speaking residents on the barricades.[9] As recollections of the barricade events indicate, for many this was a surprising and inspiring aspect of the barricade experience. A book dedicated to the barricade days issued shortly after the actual events conveys the undifferentiated unity of Latvians and Russians thought to characterize the barricades with a language and sense of immediacy not yet layered over by years of official commemorative events and state-building:

Today [in 1991] Latvians are a minority in Rīga, only 36.5% of the total number of Rigans. However, the days of the barricades attested that in Latvia one people does not stand against another [tauta nestāv pret tautu], but rather that supporters of the future and democracy stand against the forces of empire and totalitarianism. […] During those days, Rīga lived in other, irrational dimensions.[…] There was something cosmic in the air—the cold winter sky, silhouettes around bonfires, wood, trucks, singing of men’s choirs, folklore of the barricades, political cartoons on the wooden walls—all merged in unity, and that was Rīga. (LKF 2001)

While Rīga’s barricades literally paved the way for the formation of the post-Soviet Latvian state, they also produced a collective cohesiveness that for a moment rendered the tauta as a “cosmic“ force whose unity surprised not only the Soviet military forces, but the participants of the barricades themselves (LKF 2001). Thus, in addition to conjuring up the nation, these practices of barricade construction and manning also produced a very particular mode of togetherness, which we here refer to as barricade sociality. For example, Teodors Eniņš, a former deputy of the Supreme Soviet, recalls how an elderly Russian lady unwrapped a couple of pastries from her handkerchief and offered them to the people on the barricades (Kazans 2008, Daugmalis 2001a). Guntars Ļaudams recalls a similar moment during one night on the barricades:

When all the worries had passed, we calmed down and suddenly felt very hungry. And then, around 4 am, three elderly ladies appeared as if out of nowhere. They carried two large baskets full of sandwiches and two thermoses with linden tea. We were surprised that they were Russian. One of the ladies said that we were still children and started taking care of us. She fixed someone’s hat, someone else’s scarf, and urged us to eat. They told us not to worry and eat, because the food is not poisoned. We can eat all of it, they said, because other women are taking care of people on other barricades. And so we had to finish everything that was in the baskets, because they would not leave until we did (Daugmalis 2001a:91).

The barricades created togetherness in place of what seemed to have been a deep division. The elderly Russian ladies emphasized that the food they brought was not poisoned, suggesting that their gesture might have been perceived with suspicion under other circumstances. The people of the barricades had a sense that they must eat the food, for then and there these unknown elderly Russian ladies had become their motherly caretakers.

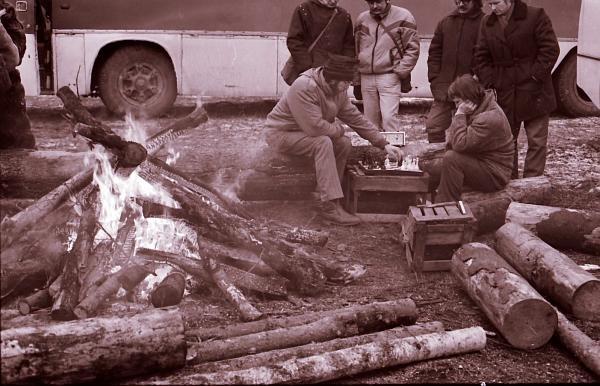

The sense of togetherness extended beyond interethnic relations. One eyewitness notes how the streets of Rīga had never seen such hospitality and politeness (Valters 2005, Daugmalis 2001a). On the barricades, people joked, sang, and danced, all the while retaining the awareness that any minute they may have to take their positions to mount non-violent resistance to Soviet military units. People listened to the radio to find out about the political climate, and information about occurences on other barricades traveled by word of mouth. Bonfires burned into early morning hours, people brought food and tea, and the singing and dancing kept the spirits up and the bodies warm in those January days of 1991 (Images 3 and 4).

While here entangled with political imaginaries of national self-determination, barricade sociality, we suggest, nonetheless elides state-based understandings of collectivities, such as that of the nation. Drawing on de Certeau’s (1984) notion of pedestrian practices and the bewitching world of the city, we suggest that a pedestrian kind of sociality is constituted on the barricades. This sociality is a dynamic formation, a togetherness in practice, which is sufficiently different from the nation as an imagined community (Anderson 1983).

|

|

While the collectivity engendered by the sociality of barricades may also be imagined, it is constituted through imagining concrete practices of building, guarding, fetching food, huddling, singing, and so forth. While it may also be one that involves strangers, it is specific strangers that one encounters on the barricades. Moreover, barricade sociality is constituted primarily through a concrete event—limited in time and space—rather than through the temporality of circulation characteristic of formations such as nations and publics (Anderson 1983; Warner 2005). In the moment of its emergence, the sense of a barricade sociality is conjured up through the immediacy of experience and word-of-mouth knowledge of the existence of other such experiences and dynamics. Significantly, such a pedestrian or barricade sociality is a form of collective subjectivity that is constituted by and constitutive of collective agency, rather than merely being experienced at the individual level as a particularly rewarding experience of solidarity, although this may of course also be the case. It is this dynamic, the force generated by people’s solidarity in extraordinary conditions, that is seen to engender hope for the future and give birth to seemingly unlimited political possibilities. As seen during the tensions surrounding Latvia’s pride parades, as well as during subsequent recollections of the barricade experience, the barricades provide a sense of a past solidarity, as well as a sense of foregone future possibilities, against which the present, including the state of the polity and the life of the people, are assessed.

Barricade Sociality and the Making of el Pueblo in Oaxaca

In May of 2006, as has been the custom for over two decades, the teacher’s union erected a tent city in Oaxaca’s zócalo, or main plaza, to hold an annual plantón, or sit-in, as a way to pressure the government for better working conditions. Typically resolved through negotiations, in the early morning hours of June 14th governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz sent in 3,000 state police armed with riot shields, clubs, and tear gas to break up the plantón. While initially caught by surprise, teachers regrouped in the streets around the zócalo and, now joined by others who had heard of the police repression, retook the space that morning. In the following days, what began as a teacher’s strike rapidly became a broader movement including students, campesinos (peasants or farm workers), unions, the indigenous community, and over 200 left-leaning groups all calling for the governor’s resignation. The Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca, or APPO, as this assemblage came to be known, regularly held massive marches through Oaxaca’s streets, took over local radio and television stations to broadcast their political messages, and used barricades to block city streets and take over the historic center. In late August of 2006, after paramilitary groups in moving vehicles shot at a radio station and killed an APPO member, barricades were quickly and spontaneously erected all over the city at night to protect against the government’s “convoys of death.”

With estimates of well over 1,500 barricades having been simultaneously set up in the city, the sweaty work of carting old tires, wooden logs, broken cement, and sand bags to create the barricades was largely done by neighbors who sought to defend their streets and neighborhoods primarily from the threat of state-sponsored, right-wing paramilitary forces, but also from the threat of robbers in a city effectively evacuated by the police. If in Latvia the barricades were concentrated at key sites as a means of defense from Soviet military incursions, in Oaxaca the neighborhood scale and location of most of the barricades resulted not only in different material practices, but also in a differently configured political imagination of the possibilities engendered by its barricade sociality.

First and foremost, as barricades spread throughout the city, the conflict not only spilled beyond the borders of the city center but also pulled in many individuals who up to that point had remained on the sidelines. As Douglas (2008) writes about France, barricades in Oaxaca did indeed succeed in converting observers into participants. However, if up to that point participants could be framed as either being members of the APPO or against the APPO, Oaxaca’s barricades delimited zones of inclusion and exclusion that did not necessarily map onto this binary opposition. That is to say, not all barricade participants supported or affiliated themselves with the APPO. Rather, they identified with and were identified by the location of their barricade and with other “barrikaderos.” At the scale of the city, barrikaderos were united by the common practice of erecting barricades out of the rubble of the city, of manning the barricades from dusk to dawn, of huddling together to listen to the radio for updates, and of checking the skies for the fireworks that announced particular trouble spots in need of immediate help.

Mark Traugott (1993) writes of how barricade participants in Paris could identify themselves as a collective “we” in relation to a long history of French revolutionary practice; as in Paris or Rīga, the collective identity of barricade participants in Oaxaca was the result of the specific articulation of the political and material conditions of that particular place and moment. Though barricades were a new practice in Oaxaca, this does not mean that the 2006 movement was not framed historically; on the contrary, the events of 2006 were at times spoken of as the “comuna de Oaxaca”—a direct reference to the commune of France—and historical figures such as Che Guevara and the revolutionary Mexican fighter Emiliano Zapata figured prominently. Indeed, as Mama Lucha, a highly active and visible participant later told Iván Arenas, there was a sense amongst those participating in the barricades that they were “making history, fighting for Oaxaca, for a new world.” This sense of historical agency, we want to argue, is not merely the product of an acute awareness of political history or of the gravity of any movement which seeks to overthrow those in power, but is itself a product of the socio-material practices of building barricades, as this congeals into the sense of togetherness that we call barricade sociality.

In Oaxaca, it had been a long-standing political practice for groups to close off streets in order to gain the attention of the media and of broader society for a particular issue or demand. Nevertheless, the barricades of 2006 were in effect an innovative practice. A popular song, entitled “To the Front Line of the Barricades,” highlights the emergent nature of the barricades by instructing individuals how to build them:

The lyrics of the song point to how the material and social practice of barricade building was still being worked out. The song’s refrain, which begins “to the front line of the barricades / with all the neighbors, with the whole family,” narrates a common feature of Oaxaca’s barricades, namely that their sociability was built around the core of families and neighbors. Most importantly, unlike Latvia, where people from all across the nation came together to form heavily-fortified and semi-permanent barricades at a centralized location, in Oaxaca most barricades were highly temporary structures erected daily by families and neighbors to close off their streets in the evening, and were taken down in the morning.

Composed day in and day out from the collected rubble of their particular street for a period spanning many months, as a material practice Oaxaca’s barricades were important spaces which fostered novel encounters and dialogues between individuals who may have lived next to each other all their lives but had never truly spoken to each other. As an editor of the popular magazine La Barrikada told Iván Arenas, his barricade, Calicanto, was “a space of intercommunitary communion, dialogue, and communication.” Though it can be written about, the visceral and lived sense of the barricades that composed this togetherness is elusive. Imagine, if you will, then, that dusk is arriving, with the sun dropping behind the mountains, you are carrying a bag of cement to the middle of an intersection. Some other day, you hope to use that cement to build an addition to your house. Another neighbor brings some old logs from a tree in his yard, others bring leftover bricks. A man who works as a mechanic brings some used tires. Everyone stacks these across the street, blocking the way to traffic. As the dark settles and the cold comes, a bonfire is started near the barricade. Those whom the group has decided should stay for the night huddle closer, those who will take the watch on another night go home to rest. As with thousands of others across the city, you turn on the radio and listen for updates. You talk with the others about the conflict, about your families, about the cold. A song comes on between the news bulletins, and everyone sings along. A neighbor drops by with food and hot coffee for everyone. You make sure that your small barricade has some fireworks handy in case there is a need to signal to others. You doze a little. As morning approaches, new coffee and food arrives, and as the first rays of the morning settle upon the rooftops, you and the others are busy collecting the materials that made up the barricade. Luckily, the death squads were far from your street that night. You go home to rest a little before thinking about going to work.

As with many cities in Latin America, Oaxaca may be well known for its colonial center, but the bulk of the population lives either in well-off communities where electrified wires and 12-foot fences separate homes, or in poor shanty-towns which grow haphazardly in the perimeters of the city. Whether through such fortified walls or via the unpassable dirt roads and social stigma that effectively form moats around poor areas and poor populations, Oaxaca’s city spaces are largely zones of exclusion. From Friedrich Engels (2009 [1844]) and Jane Jacobs (1993 [1961]) to Walter Benjamin (1999 [1982]) and Teresa Caldeira (2000), many scholars have both lamented and analyzed the way in which modern cities are formed by collectivities of abstract strangers who may pass or gaze at each other daily but do not effectively see or know each other. Though differently configured, whether one looks at France, Latvia, or Oaxaca, the barricade sociality engendered by the visceral nature of barricade construction, by the consequential demands of manning and maintaining them, and via the social bonds that these forge, constructs shared social experiences and imaginaries that radically transform the abstract modern city and its social relations.

Through the takeover of the zócalo, the barricades, general assemblies, and marches involving millions in the streets, Oaxaca’s movement of 2006 reconstituted what had up to then been abstractly termed public spaces into places of and for el pueblo. It is important to note that, in Spanish, el pueblo has the dual connotation of referring to both “the people” and “the town.”[10] The articulation of a socio-spatial connection is an apt one to describe the work done by the signifier of el pueblo with regard to the abstract notion of the public. Composed of myriad individuals with a wide range of experiences, ages, and points of view, the barricade sociality that was forged through the long and dangerous Oaxacan nights was built upon practices that made the recognition and acknowledgement of difference into an important component in the communal assemblage that came to be identified as el pueblo. Grounded in a particular place, el pueblo is the local community constituted not through abstract discourses of belonging but rather through concrete material practices that construct shared social experiences and imaginaries.

Re-Articulating Latvia’s Political Imaginaries in the Aftermath of the Barricades

In Latvia, the sociality of the barricades and of the independence struggles more broadly, or rather perhaps the promises that are attributed to it, are today invoked by those who feel excluded from the people-cum-political nation that was the subject and object of politics during the days of the barricades. It is common to hear stories about and from many Russian or Russian-speaking residents of Latvia who now feel offended because they were part of the people of the barricades only later to be designated as non-citizens, as non-members of the very same polity whose future possibility was being protected during those nights on the barricades.

Despite the promise of the so-called zero-citizenship option put forth by Latvian politicians during the independence struggles of the late 1980s, whereby citizenship would be granted to all residents living in the territory of Latvia at the time of independence, Latvian politicians were weary to follow through on the promise once political independence was achieved, for fear that the loyalties of Soviet-era Russian-speaking incomers ultimately lay elsewhere. The political leaders of the late 1980s and early 1990s thus chose to correct the injustice of Soviet occupation by legally restoring the prewar Latvian state (1918–1940) rather than conceiving of the post-Soviet Latvian state as a new entity. The restoration of the pre-World War II body politic meant that the new body of citizens was constituted from those who could establish a direct or descent-based relationship to the interwar body of citizens, which consisted of various ethnic groups, including Russians who resided in Latvia prior to the Soviet occupation. The multiethnic make-up of the pre-Soviet body of citizens derived from the fact that the first independent Latvian state granted citizenship to all residents of the Russian Empire who resided in the territory of Latvia prior to World War I. Thus the division between citizens and non-citizens instituted by the post-Soviet Latvian state does not map onto specific ethnic groups. As a result of the post-Soviet Latvian state’s citizenship policy, about 329,000 of Latvia’s current residents (out of 2.4 million) are still citizens neither of Latvia nor of any other state.[11] They are, however, tied to the Latvian state through the political institution of non-citizenship, which emerged as a compromise in the early 1990s between variously oriented political forces and international organizations.[12]

The political institution of non-citizenship posits Latvia’s non-citizens as “candidates for citizenship” much like the European Union designated Latvia and other Eastern European states as “candidates for membership” following the collapse of Eastern European and Soviet socialism. Latvia’s non-citizens are thus folded into the state’s protective and regulative apparatus, yet are required to meet a set of criteria and undergo naturalization in order to become full members of the polity. Distinct from resident aliens whose stay in Latvia is temporary, resident non-citizens have a right to permanent residence and the same social and economic rights and protections as citizens, including consular protection. At the moment, the most contested legal difference between citizens and non-citizens pertains to the latter’s inability to vote in local elections, though there are others, such as the inability to occupy certain civil service positions that have to do with state security, or to join the military (Reine 2007). The difference in voting rights is thought of as especially unfair, since citizens of other European Union member states, many of whom reside in Latvia for significantly shorter periods of time than most Russian-speaking resident non-citizens, are entitled to participate in local elections if they register as residents of Latvia three months prior to the election.

Naturalization requirements in Latvia do not differ much from those of other countries—individuals are required to fulfill a residency requirement (which no longer applies to those who were residents of Latvia prior to 1991, or to those born in Latvia), to express a desire to become members of the polity by applying for citizenship, to pay a state tax, and to pass an exam which tests their Latvian language skills, knowledge of the national anthem, and knowledge of Latvia’s history and Constitution. What introduces a difference, however, is the perceived injustice of the requirement to undergo the naturalization process for people who have lived in the territory of what is now Latvia for decades or were born in it prior to 1991 and thus do not have any real ties with other states. The resentment is especially strong among those who were on the barricades or were otherwise strong supporters of the independence struggles, but who subsequently found themselves excluded from the polity.[13]

The particular material practices, bodies, and politics that composed Latvia’s barricade sociality were articulated in ways that that conjured up the people as an almost cosmic force that could rise against the Soviet military. In the years that followed independence, this gave way to a state-based form of nation-building, where dividing lines were drawn between majorities and minorities, whether ethnic, sexual, or otherwise. The practices of state-building that are inscribed into the form of the modern nation-state introduced an important distance from spontaneous and effervescent formations—such as barricade sociality—and divided the population. Current divisions between the majority and minorities or between citizens, non-citizens, and resident aliens could have been drawn differently; the precise lines of division are therefore the product of specific historical circumstances. However, we would argue that the fact of division itself is built into the modern nation-state form. Similar to the way in which every act of remembering is also an act of forgetting, we might say that every act of inclusion is also an act of exclusion. To put it another way, we are suggesting that the politically enabling aspects of barricade sociality in Latvia were not limited only by the exclusive conceptions of the nation as a people (Volk) that animated the independence movement. Rather, we argue that in the years following independence, the articulation of the political imaginary of national self-determination and the barricade sociality that characterized independence struggles was transformed. This happened through a re-articulation of the political imaginary of national self-determination with the modern nation-state form, which demanded that lines be drawn around a body of citizens and between a majority and minorities. In the process, the nation, too, took on increasingly exclusive contours. We therefore suggest that in analyzing modern nation- and state-building in Latvia, it might be useful to shift the focus from the always-already exclusive and nationalistic political imaginary that is often said to characterize public and political life in Latvia, to an emphasis on the articulation of the nation with modern practices of statecraft. We also suggest that this articulation might be what contributes to the emergence of the exclusionary and dividing politics which constitute the current “moment of danger” to which many in Latvia have responded by conjuring up romanticized imaginaries of the barricades and the seemingly endless political possibilities they engendered.

Hailing el Pueblo in the Aftermath of Oaxaca’s Barricades

The form of urban warfare being practiced today is not as direct as that seen in the confrontations of 2006 between government forces and the APPO. Yet barricade sociality remains an important condition of possibility and groundwork for current struggles in Oaxaca. Fought with words and images spray-painted at night on the façades of the city which are then painted over during the day, today’s street warfare may seem more ephemeral, yet the trenches are just as acutely drawn and the political and social stakes are just as high. From fascist robots slaughtering innocent chickens to grasshoppers in gas-masks surrounded by fields colonized by transgenic corn, and from commemorative images marking important battles with police to larger-than-life images of those who have died or remain political prisoners, the clear-cut aesthetic and socio-political message of politicized street art in Oaxaca has made quite a visual impression upon Oaxacan walls and minds.

Significantly, the general extent of this contested socio-aesthetic arena closely maps onto the contours of Oaxaca’s historic city center, which has over 500 years of sedimented histories. The center is a focal point of the city’s social activity and historical image and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. Whether in newspapers, television, or the radio, and whether from architects, the archbishop, or government dignitaries, much of the official discourse about the visual and social state of the city center returns to the question of the harm that is being done by street art to the heritage of all Oaxaqueños. In contradistinction to the ways in which, at its broadest, referencing el pueblo marks out the collective subject position of all the individuals who were involved or would have affinities with the social movement of 2006, Oaxaqueño is meant to designate a more inclusive collective which would encompass everyone who lives in Oaxaca or who identifies themselves as Oaxacan. However, though it marks out the public spaces of the city center as being the heritage of all Oaxacans, official discourse (and police practices) make it clear that not every Oaxacan or every form of local expression is welcome there.

In contrast, political street artists make sharp distinctions between public space and the particular public they wish to reach. As one street artist collective put it,

visual resistance is our weapon [...] We express that which comes from inside, not only from the heart, but also from our conscience, and all of this sentiment is transferred to images that travel through our memory. In all of this being placed on the street, it reaches everyone, from the poorest to the richest. Our goal is to reach el pueblo, because we are part of it, we live with it, and we want something better for it. (ArteJaguar 2007)

Though stencils mark the skin of Oaxaca like tattoos, aesthetic considerations are not their primary end. Rather, the images are meant to connect to and to move particular viewers by articulating the ethical and the poetical. Speaking from the perspective of shared experiences and practices such as those formed during the barricades, images and messages on city center walls are meant to incite el pueblo to reflect on its conditions and to act to transform them. Though visible to all who pass by, politicized street art looks to hail and interpellate the particular public of el pueblo (Images 5 and 6).

In the absence of the barricades themselves, images of the carts filled with stones, Molotov cocktails, or home-made rockets that were used during struggles with police interpellate el pueblo by way of the circulation and reiteration of images

|

|

Conclusion

We hope that is has become clear from the examples above that even as barricade sociality enabled the collectivity of the tauta or el pueblo to come into being as a collective subject position, the togetherness-in-practice of barricade sociality always-already exceeded this collective subject position; thus, while certain places and discourses may continue to interpellate the tauta or el pueblo—often explicitly making a reference to the sociality forged in the barricades—the congealing of this dynamic sociality into a particular subject position also means that the social and political openness which characterizes barricade sociality becomes enclosed, even if never fully foreclosed. The collective subjectivity engendered by the visceral togetherness of barricade sociality entails great possibilities, but equally serious limitations. It is and perhaps always will be ephemeral—it is not possible to recreate it simply by putting up barricades, faking a crisis, or producing a discourse about it. And yet the longing or lament for that moment of openness, as well as the closures produced by it, have important political and social implications, not the least of which is in identifying a critical lack in our modern conventional social bonds and the desire for another way of being in communion with our neighbors.

At the moment, Latvia is once again experiencing a crisis.[14] With the economy shrinking by 18% in 2009, with unemployment at 18%, and with a budget that cut spending by 40% and instituted pay cuts for state employees of around 20%, in December 2009 Latvia received an emergency 7.5 billion euro loan from the IMF as part of an ongoing economic restructuring package.[15] In response to the economic crisis and as a result of the widespread popular resentment toward governing parties, several mass demonstrations have been held in Latvia in recent years. Some of them—such as the call for the tauta to gather in the Dome Square in November of 2007—conjured up associations with the barricades of 1991 insofar as they aimed to create the kind of sociality that many thought had disappeared with the barricades and which many hoped could be reignited and harnessed to change current government practices. At the square, the tauta was summoned to sing, a symbolic and political act that has long been identified almost exclusively with Latvians.[16] As such, this attempt to conjure up an enabling sociality of the people was shaped by post-barricade years of nation-building which rendered it an explicitly Latvian phenomenon—so much so that many non-Latvians at the Dome Square who otherwise shared the sentiment of dissatisfaction did not join in.[17]

In Mexico, which is experiencing its deepest recession since the 1994–95 crisis, the plummeting currency and loss of steady remittances from the United States led the government to set up an approved credit line in April, 2009, of 47 billion dollars from the IMF. While the Mexican government has not drawn from this credit, and while the currency has reversed its downward trend, few in power have questioned the implications of IMF oversight. It seems that neoliberal market reforms continue to shape the future horizons of both Mexico and Latvia. Yet, on the streets of Oaxaca, important changes have been registered. In the 2007 municipal elections, for example, 70% of eligible voters in Oaxaca abstained from the polls. As many people told Iván Arenas, and as the media reported, Oaxacans had lost faith in representative democracy and were seeking alternative ways of organizing and participating in politics. For many, this meant reimagining politics as an active space and process for making decisions at the level of the community rather than at the level of the city, state, or nation. As the effects of the 2006 movement in Oaxaca continue to be felt, and as the recent political protests in Latvia show, on the street, in very pedestrian and mundane ways, albeit not in conditions of their own choosing, people in both countries are rethinking what the future might look like.

Looking out onto Manhattan from what was the 107th floor of the World Trade Center, de Certeau finds that the planner’s gaze “creates the fiction of knowledge” (1984:123) by transforming the chaotic reality of embodied streets into a scopic vista devoid of struggles or contradictions. In contrast, de Certeau posits the indeterminate and uncountable spatial practices of the inhabited city as a sphere that not only resists but also effectively reconfigures the planner’s abstract perspective. If Marx famously stated that men make history, though not under conditions of their own choosing, de Certeau reminds us that politics are enacted daily by everyone in the micropractices that make up the socio-material entanglements of every place. While the outcome of these practices may not be certain, and while their capacity for transformation may seem fleeting, it is precisely because these collective stories are wrapped in contingency that they are so powerful. Though it might be tempting to dismiss them as forgettable or failed insurrections, Latvian and Oaxacan experiences with barricades are generative because they show us that political possibilities can be harnessed from pedestrian practices that emerge at the intersection of historical sedimentations and the hegemony of neoliberal market reforms and liberal democratization discourses.

References

- Althusser, Louis. 1971 [1970]. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation).” Pp. 127-186 in: Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Translated by Ben Brewster. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1996 [1983]. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

- Aquino Casas, Arnulfo. 2007. [No title]. Resortera: fanzine callejero no. cero. Oaxaca: ASARO, November.

- ArteJaguar. 2007. “ArteJaguar.” In Stencilatinoamerica: iconografia callejera. Oaxaca: La Curtiduria.

- Beliaev, Alexandre, and Dace Dzenovska. 2009. “Some Reflections on the ‘Global’ Crisis in Latvia.” Newsletter of the Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, University of California, Berkeley 26(2):3–6.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1999 [1982] The Arcades Project. Edited by Rolf Tiedemann, translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1988 [1950]. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Pp. 253-264 in: Illuminations. Edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge.

- Caldeira, Teresa. 2000. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in São Paulo. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Daugmalis, Viktors (ed). 2001a. Barikādes: Latvijas mīlestības grāmata [Barricades: The Latvian Love Story]. Rīga: Barikāžu atbalsta fonds.

- Daugmalis, Viktors. 2001b. Barikādes. Rīga: Barikāžu atbalsta fonds.

- Douglas, Carl. 2008. “Barricades and Boulevards: Material transformations of Paris, 1795–1871.” Interstices. Journal of Architecture and Related Arts 8:31–42.

- Dzenovska, Dace. 2009. Provoking Tolerance: History, Sense of Self, and Difference in Latvia. PhD Dissertation. University of California, Berkeley.

- Dzenovska, Dace. 2007. “Neoliberal Imaginations, Subject Formation and Other National Things in Latvia, the Land that Sings.” Pp. 114–138 in: Representations on the Margins of Europe: Politics and Identities in the Baltic and South Caucasian States. Edited by Tsypylma Darieva and Wolfgang Kaschuba. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

- Engels, Friedrich. 2009 [1844]. The Condition of the Working Class in England. London: Oxford University Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 2000 [1982]. “The Subject and Power, and Space, Knowledge, and Power.” In: Essential Works of Foucault, Volume 3 (Power, edited by James D. Faubion). Edited by Paul Rabinow. New York: The New Press.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1998 [1992]. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Avon Books, Inc.

- Jacobs, Jane. 1993 [1961]. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, Inc.

- Kazans, Jānis. 2008. “Ko glabā to dienu atmiņas?“ [What do the memories of of those days preserve?]. www.liepajniekiem.lv/lat/zinas/aktuali/2008/01/17/pagtne-ietamba-stenba/

- Hall, Stuart. 2003. “Marx’s Notes on Method: A ‘Reading’ of the ‘1857 Introduction.’ Cultural Studies 17(2):113–149.

- Hall, Stuart. 2002. “Race, Articulation, and Societies Structured in Dominance.” Pp. 38–68 in: Race Critical Theories. Edited by Philomena Essed and David Theo Goldberg. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

- Latour, Bruno. 1999. “Circulating Reference.” In: Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2000. “Articulating Indigenous Identity in Indonesia: Resource Politics and the Tribal Slot.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 42:149–179.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1995 [1974]. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers Inc.

- LKF [Latvijas Kultūras Fonds]. 1991. 1991. gada janvāris Latvijā [January of 1991 in Latvia]. Rīga.

- Malkki, Liisa. 1995. Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology Among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Marx, Karl. 1977 [1857]. “General Introduction.” Pp. 345–360 in: McLellan, David, ed. Karl Marx: Selected Writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Miller, Daniel (ed.). 2005. Materiality. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Nagle, Ilze. 2007. “Naids kā sāpīgs bumerangs” [Hatred as a painful bumerang]. Sestdiena, 2 July.

- Ozoliņš, Gatis. 2008. “Šķīrāmies nesatikušies” [We parted without having met]. politika.lv (www.politika.lv/temas/pilsoniska_sabiedriba/17012/)

- Puriņš, Gatis, and Uģis Šulcs. 2002. “Etnisko balsojumu diskrētais šarms” [The discrete charm of the ethnic vote]. politika.lv. Online at: www.politika.lv/temas/7623/ (accessed January 2010).

- Reine, Inga. 2007. Protection of Stateless Persons in Latvia. Paper presented at the Seminar for Prevention of Statelessness and Protection of Stateless Persons within the European Union, European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice, and Home Affairs, June, 26.

- Said, Edward. 1994 [1978]. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

- Silova, Iveta. 2006. From the Sites of Occupation to Symbols of Multiculturalism: Reconceptualizing Minority Education in Post-Soviet Latvia. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing.

- Traugott, Mark. 2010. The Insurgent Barricade. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Traugott, Mark. 1993. “Barricades as Repertoire: Continuities and Discontinuities in the History of French Contention.” Social Science History 17(2):309–323.

- Valters, Raits. 2005. “Raita Valtera atmiņas par barikādem“ [The Barricade Memories of Raits Valters]. Latvijas Avīze. January 11. www.apollo.lv/portal/news/articles/38696.

- Warner, Michael. 2005. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

-

See Mark Traugott’s forthcoming book The Insurgent Barricade (2010) for a detailed historical analysis of the Parisian barricades, as well as of the barricade event as a political and social phenomenon. ↩

-

Douglas does note that some instances of barricade-building appeared in the middle of the20th century (1968 in Paris, for example), but argues that the practice has lost its revolutionary prominence. ↩

-

Though relatively short-lived, the barricades created new relationships between people, spaces, and people in spaces. Over time, these solidifi ed into particular subjective identifi cations that continue to defi ne those people and places. Which is not to say that, as these have congealed, they have stayed the same; on the contrary, they are continually being renegotiated. This is why we have found it useful to draw explicitly on Stuart Hall’s conception of articulation (2002) as a fl exible joint or constructed linkage that is, as Tania Murray Li succinctly notes, also “subject to contestation, uncertainty, risk, and the possibility of future articulation” (2000:169). ↩

-

We would like to thank Gillian Hart for introducing us to Stuart Hall’s reading of the “1857 Introduction.” ↩

-

Independence struggles in 1991 were conceived in the idiom of renewing the independent Republic of Latvia which existed between 1918 and 1940. This way of conceiving of the polity was not only symbolic, but also resulted in concrete policies, such as strict citizenship laws, which excluded many of those who participated in the 1991 barricades from the polity they helped to (re)make. ↩

-

Several of the major demonstrations of the late 1980s occurred on the riverbank (krastmala). The independence struggles of the late 1980s are known as the Third Awakening, with the First Awakening occuring during the second half of the 19th century when young Latvian intellectuals (Young Latvians or Jaunlatviesi) embarked upon nation-building efforts. The Second Awakening marks the period following the 1905 Revolution and leading up to the World War I and, subsequently, marks the establishment of the fi rst independent Latvian state. ↩

-

The Popular Front, a moderate political force at the forefront of the independence movement, gained 124 of the 201 seats in the Supreme Soviet, which ensured that the motion for independence passed. In the pre-election period, the Popular Front appealed to all residents of Latvia and did not differentiate between former citizens of the fi rst republic and Soviet-era migrants, which endowed them with the support necessary to be overwhelmingly elected to the Supreme Soviet. See Silova 2006 for a discussion of the pre-election strategies of the Popular Front in relation to Latvia’s Russian-speaking residents. ↩

-

Barricades were also constructed in Liepaja, a former military port. However, the barricades in Riga drew many more people and, arguably, played a much more central political role. ↩

-

This effort was successful insofar as 73.8% of the population voted for independence in a national referendum held in March 1991 (participation reached 87% of the population). This was noteworthy, given that due to Soviet practices of population transfers, the proportion of Latvians in the territory of Latvia had decreased from about 75.5% in 1935 to about 52% at the time of independence. See www.li.lv and http://countrystudies.us/latvia/9.htm. The view that Latvian independence was widely supported across ethnic divisions holds strong in popular discourse today; however, some have contested it by statistically showing that that it was mostly ethnic Latvians who voted for independence (Purins and Sulcs 2002). ↩

-

While the complexities of the particular genealogy of el pueblo, both as a concept and in its historical usage, is beyond the scope of this paper, its history in defi ning oppositional and consequential inclusions is important. In one era, el pueblo defi nes the way in which Spanish settlers referred to colonial settlements as differentiated from native communities and from the un-civilized “wilderness.” In anti-colonial movements in Spanish America, it comes to defi ne the people fi ghting for sovereignty as they forged a new nation. Today, plural usage of the term (los pueblos) often marks the recognition of the multiple ethnic groups that make up the modern Mexican nation at the same time as it stakes a claim to varying degrees of desired cultural or political autonomy from the nation-state. ↩

-

Since the beginning of the naturalization process, about 150,000 people have obtained Latvian citizenship either through naturalization, by registering children born after 1999 or young adults who have graduated from a Latvian language high-school. (www.np.gov.lv/index. php?id=440&top=440). ↩

-

Ruta Marjasa, personal communication 2008; Leo Dribins, personal communication, 2005. ↩

-

See Silova 2006 for a discussion of political strategies of the Popular Front in this regard. See also Dzenovska 2009 for a more extended analysis of contemporary public and political life in Latvia. ↩

-

See Beliaev and Dzenovska 2009 for a critical engagement with discourses of crisis in and about Latvia. ↩

-

See www.imf.org/external/country/LVA/index.htm?pn=2. ↩

-

In the late 1990s, the Latvian Institute—a state agency entrusted with the task of compiling and disseminating information about Latvia at home and abroad—the Latvian Development Agency, and the Latvian Tourism Agency were involved in promoting an image of Latvia that would appeal to investors and tourists respectively and for a while considered branding Latvia as “The Land that Sings” (see Dzenovska 2007). ↩

-

It should be noted, however, that even some Latvians expressed dissatisfaction with the emphasis on singing. Following the November 2007 manifestation, also known as tautas sapulce (the meeting of the people), a teacher wrote an open letter to some of the opposition politicians who had organized the event (Ozolins 2008). He expressed his dissatisfaction that he came all the way to Riga from the country to stand in the Dome Square and sing and that therefore nothing was resolved, no decisions were made, and no lasting ties established. The people at the gathering, as he noted, did not even meet each other. ↩